My fraternal twin Audrey has written a many notes on what our father said about his life and I will only quote a few portions. I have kept mainly to what relates to Captain John Francis Hyde and Hyde End.

Slough and London 1894-1895:

"Although Father owned Hyde End, it never crossed his mind to sell the Estates and buy elsewhere. Instead he rented houses wherever the whim would take him. He was nearly 70 when I was born in a rented home, at Clifton Grove, in Slough.

My mother was very ill, after my birth, so I was sent to Hyde End and lodged with the Gatehouse Keepers wife. She was able to nurse both her baby, and myself...."

"...At about eight months old, I was taken back to Slough.

One of my earliest recollections, is lying on a bed, dressed in petticoats, and watching a bright light at the window. Suddenly I was snatched up, by my Nanny, and whisked out of the room. The curtains had billowed in with the breeze, from the open window, and covered the flame of the spirit lamp Mother used for her curling tongs, thus setting the curtains ablaze...."

"...Some children have cuddle rugs, or Teddy bears, they can't be parted from. My constant companion was a broken-off arm of a chair, upholstered with a flowery patterned material. I can't remember now, what happened to it, but I still had it when we went to Margate.

I was about 18 months old when we went to London. The city then, was a grimy place and the houses had large dingy rooms, stuffed with ugly Victorian furniture. Large dour looking people, in portraits, would stare down at you, and one felt their staring eyes following you around the room. Quite intimidating to a small child. The bedrooms had the usual huge brass bed; china wash basin and large china jug.

The arrival of the petrol engine had occurred, although the streets were still full of horses and various types of carriages...."

"...After the stay in London, I had my first train ride. My parents had leased a guest house in Margate, and here I was to have the happiest days of my childhood."

Return to List

Margate and Hyde End 1899-1902:

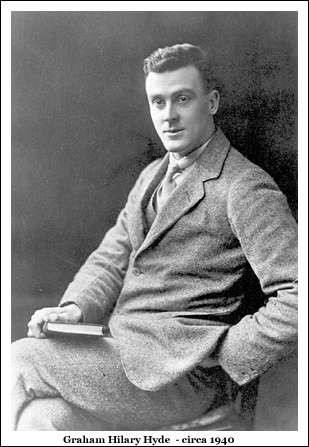

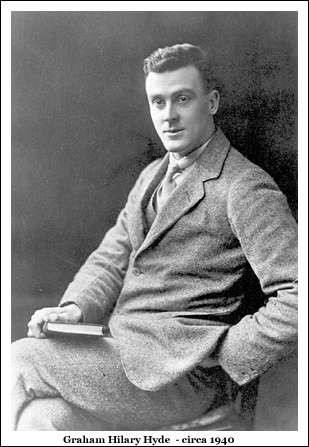

"Although baptised Graham Hill Hyde, the Hill after my Godfather, Admiral Hill, I was always called Bonny by the family. I certainly never felt bonny in the winter time, because I often had to stay in bed for weeks at a time, suffering from bronchitis. Someone always gave me a black kitten to play with, on these occasions, and this resulted in a number of black cats, of varying ages, roaming around the house...."

"...Between lettings of the mansion at Hyde End, the family, including me, would live there, while Muriel stayed back in Margate to look after the Guest house.

Summer, 1902, was to be the last visit we would make, although we didn't know it at the time.

I have very fond memories of Hyde End, and like my half brothers before me, learnt to ride and to fish the Enborne.

I was taught to shoot but had no love for the 'sport', although those early lessons were to be a boon, for me, later in Wartime.

In the mansion were reams and reams of beautiful grey note paper, with the family crest embossed in green at the top of each page. We children scribbled over the lot with no thought of the dreadful waste. Little vandals!

Father never let anyone dub his boots, but himself, and I would sit at his feet and listen to the fund of stories he had, about the family, while he rubbed the dubbing in to make the boot leather soft. He would spend hours telling me the stories and I wish tape recorders were in existence then; as I have forgotten so many of them.

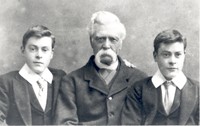

In 1902 he was aged 76, but to me he wasn't an old man, as he still had a good seat on a horse, walked well, and had a good mind.

Mothers cottages, 'The Birches', were occupied by people called Bousfield. They bred rabbits, and I enjoyed going there to help feed and look after them. Fortunately, I never realised they were being bred for the pot, or I would have never gone near the place.

One of our Tenant farmers taught me how to milk a cow by hand. No mechanical milking machines, in those days. An average sized herd would be about 20 cows, to enable a family to make a decent living. Most Tenants kept pigs, chickens and geese, and all had vegetable gardens, so they were pretty much self sufficient and reasonably well-off, but it was a hard life for the labourers. They literally had to count every penny, although they never grumbled and seemed happy with their lot.

It was accepted, that the rich and poor equally, had their place in society, and no one ever questioned it This had been the established pattern for centuries, but it was all to change with the arrival of the 20th century.

The Tenants kept us supplied with fresh produce, while we were in residence, including homemade butter, and lovely fresh thick cream. There is nothing more delicious than freshly picked strawberries, smothered with freshly made cream.

I was the only one in the family to have any leanings towards farm life, and if I had been the eldest, I would have certainly kept Hyde End going as a viable concern.

Alas I was at the bottom of the rung, so had no claims on the property. All I can do is look back on Hyde End with nostalgia, and think about it as it was then. Now it has had a lot of its land subdivided, and the old mansion hasn't been lived in for years, thus it has deteriorated. I would hate to see it now, and can only hope and pray, some one, some day, will fix it up and bring it back to its former glory."

Return to List

Margate and Fathers Death in 1903.

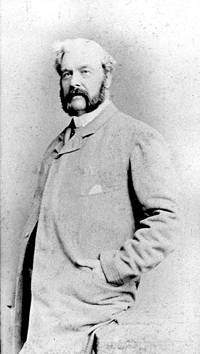

"...Over the last couple of years, Father was home most of the time, and as I was the only child still living at home, we got to know each other very well. He was a tall, gentle man, and I had great respect and admiration for him.

We went for long walks, and if Mother had her suffragette cronies around for meetings, we would amble off and visit someone, so we could be out of the way of all those women.

When smaller, after a suffragette meeting, I would sneak into the Drawing room and drink the dregs of tea left in the cups, before a Maid cleared away the dishes. Now and again, I would be lucky and score a small left over cake, so would gobble it up before anyone found me.

On a bleak September day, Father accompanied me on a walk along the cliff tops. He decided to have a rest, and told me to go ahead without him, and he would wait for me. I wandered off and didntt realise time had flown by so fast, as it was two hours before I got back to him. He was cold but soon warmed up with a brisk walk home.

Next day he developed a chill, and with each ensuing day, his health deteriorated. Two weeks later he died of pneumonia, on the 23rd September, 1903.

I was devastated, and to make matters worse, the family, excluding Jack, pointed the finger at me, and told me I was responsible for Fathers death. It was an ugly accusation for a nine year old boy to cope with.

Father had become a popular identity around town, and nearly the whole town turned out for his funeral, and a large crowd gathered outside St Johns Church where the service was held. Many had come from London, Berkshire, and many other places to pay their last respects. He is buried in the Margate Cemetery

The death of Father, was to change our lives completely...."

Return to List

School days- Slough 1904-1908:

"Back in London, no one knew what to do with me. There was no money for me to attend boarding school, and hardly enough to feed and clothe me.

Maud, Muriel and Gwen, couldn't afford to help because none of them earned very much in their various jobs.

Muriel had heard of a boarding school, in Slough, which would take orphans and children from one parent families. The schools main funding was from donations from the rich, but with her first enquiry she was told I was a 'case for the family'. This meant Mother had to approach Frank for help to send me to the school.

He flatly refused.

The school then wrote to him, and they had a very abrupt refusal, so the upshot was, I was taken in on a charitable basis. Mothers pride took a hammering, at this time, but she had to accept the situation as there was no alternative.

The name of the school was, 'The British Orphan Asylum'.

I loathed the five years I was there.

The school was run by a very harsh man, who would not let any boy forget he was there only because of the generosity of the rich. I was held up to ridicule once, by the Head Master, who hauled me up in front of the whole school, and showed everyone the patches on the seat of my pants.

Mr Gillet, was the Patron of the school, and he would invite the good looking boys for tea, in his nearby house. One day I had an invitation, but it was to be the only occasion. I detested the man, and I am sure the feeling was mutual, as he knew that by rights, I should not have been admitted to his school. I didn't enjoy the tea at all, and couldn't wait to get back to my spartan conditions, over the fence.

It was a co-educational establishment, but the girls were separated from us by a high wire fence, so never the twain should meet. However, we would eye the girls, and when older, I took a fancy to one called Berenice, but nothing came of it.

Eton wasn't far away, and whenever those boys saw any of us, they would heckle and jeer, and make us all feel like the dregs of society. It was terribly humiliating. wonder how many of those same boys fought alongside us, in Flanders?

We slept in long barren dormitories, with 24 beds in each. The iron beds had horse hair mattresses, which were hard and uncomfortable, and in the winter it would be so bitterly cold that it was a miracle no icicles formed around the bed rails. We had cold showers year round, and would be fed the barest minimum of food, so were always hungry.

Sports were compulsory, so I played cricket in the summer, which I enjoyed, and rugger in the winter. I can't say I liked that game. We also did a lot of running, long jump, high jump, etc. I surprised myself at one sports day, by winning the hurdles. My long legs helped me.

We weren't allowed to play tennis, and would envy the girls, as they gently lobbed the balls over the nets on their tennis courts. Tennis wasn't thought of as a suitable game, for boys, in those days.

The Music Master was the only teacher I liked, so I joined the choir. We would go for trips, around the district, singing to rich business and their wives at various venues, and one memorable occasion we all went to the Northumberland Hotel, in London. I say memorable, not because of the singing, but the oranges the management gave us. We gobbled them up with gusto. What a luxury oranges were to us hungry boys. We may have had the occasional apple at school, but never an orange!

I didn't get to know the Christian names of many boys, as we were always called by our surnames. My friend was a lad called Hedges, and to this day I don't know his first name.

At the age of 12, we were allowed to have our own bicycles, so Mother managed to rake up enough money to buy me one, and with permission, Hedges and I would whiz around the country lanes. It was a happy release from our sombre surroundings at school, but God help you if you were late back, as that meant a good few strokes of the cane on the bare behind, from the Head Master, and confiscation of the bicycle. We never had to face that because we always kept a good eye on the time, on our country meanders.

I tried to stay out of trouble, and this resulted in me becoming rather introverted. My solace was reading, and I would hide away in some cubby hole, and pore over books.

The words would transport me out of the place, and in my mind I would travel the world. Rudyard Kipling was a great favourite, and I enjoyed any books on the Antipodes.

The whole time I was at school, only one member of the family came to see me. Gwendoline. She arrived wearing a very elegant grey suit, with ruffles around her wrists. She looked stunning. The school staff and boys, gaped, and wouldn't believe this vision of loveliness, could possibly be the sister of this shy, awkward, lanky lad.

A year or two later, while I was at this school, Mother went to live with Jack in Lincoln, for a couple of years, then she went back to London and found cheap lodgings in Hampstead. She obtained a small job working for the 'Womens Freedom League', who had their headquarters in the Adeiphi, and was happy to be back with her old suffragette friends.

On holidays I would earn a few pennies for taking tea and cakes around to the various offices. The Secretary was a Countess DeVeine, who always lost papers and got everything completely muddled. In exasperation she'd declare, "Everything is a perfect blurr". I liked her because she was more light-hearted than many of the other ladies, and often gave me a portion of her cake to eat.

On the whole, all the ladies were kind to me, and for many years, after I left England, They would ask Mother how their Bonny was getting on.

A few well known men were starting to take an interest in the suffrage movement, and one of the most sympathetic was the Art critic, Roger Fry, who would often drop in. Ellen Terry, the famous actress, was also a frequent visitor.

Some of the ladies would invite Mother and I to musical evenings they held in their homes. On these occasions we all sat around, on hired gilt chairs, and listened to classical pieces played by professional musicians. No one would dare to even cough during these performances. We not only enjoyed the music, but also the delicious refreshments that would be passed around.

Mother and I, didn't earn much money, so I was always starving as our main diet was bread and Lyle's golden syrup. One holiday, when I was 14, we had a surprise visit from Mitchelmore. His conscience must have worried him, after seeing how hungry and pathetic I looked, so he asked Mother if he could take me out to dinner. He took me to Simpsons, which was a well-known restaurant in the Strand.

I had never seen so much food in my life, and stuffed myself, and must admit, felt quite ill later on, but it was worth it. We went home and Michelmore asked Mother if he could take me out for a meal once a week, from then on.

She would not accept his charity and refused his offer.

We never saw him again.

I finished my schooling, in 1908, at the age of fourteen and a half years, with no qualifications in anything."

Return to List

To Australia in 1909:

"School was a perfect waste of time for me, and once I had left, the old question arose. What to do with Bonny?

Sir Charles Shuckbrugh, one of the trustees of the Estates, came to visit, and unlike Michelmore (Mr Jeffrey Edwards-Michelmore), Mother had a great deal of respect for Sir Charles, and accepted his proposal to send me to Melbourne.

Many young men were leaving Britain to try their luck for a better future, on the large tracts of land that were opening up in Australia. Ways had been found to water the arid areas, thus making the land viable for various agricultural enterprises.

Sir Charles decked me out in new clothes, paid for my passage on the ship, and gave me enough money for me to get by, until I found a job. Mother wrote to Frederick and Ben to tell them of my imminent arrival, but it was 61 years later, before I learned they never received the letter. I was also given the address of Mother's first cousins, the Armitage's, who lived in Melbourne.

When I waved goodbye to Mother and my sisters, at Southhanpton, I felt very sad, and suddenly realised I was now completely on my own, and my future would be all up to me. I was a bit frightened at the prospect, and no wonder. I hadn't yet reached the age of 15, but because I was over 6ft tall, many thought I was a lot older.

I cannot remember the name of the ship, but after finding my sea-legs and overcoming my shyness, I made friends with a Scotsman, named Eric Olley. He was four years older than me, and we remained good friends until he was killed in the War.

The voyage took about two and a half months, and it was mid - summer when we sailed into Port Philip Bay. I fell in love with Melbourne, at first sight, as everything looked so colourful and bright after the drabness of London. Eric and I disembarked, and found our way into the city to the Y.M.C.A. where we obtained lodgings for a shilling each, a night...."

Return to List

First World War and the Military Cross:

"....The call went out for men over 5ft 6ins tall, aged 19 to 30, and at least 34ins about the chest. As I was over 6ft 2ins tall, 20 years old, and brawny from all the physical work I had been doing, I fitted the necessary requirements.

After a check up by Dr Henderson, at the local hospital, I bid farewell to my friends and headed for Melbourne to enlist.

Enlisting on the 24th of September, 1914, I was among the first of three hundred men who went to War from Mildura...."

At Gallipoli 1915:

"...I had an extraordinary experience on one of my swims. I did a duck-dive, to dodge bullets, and spotted a cartridge sitting on the ocean floor. On closer inspection, I was amazed to read my regimental number, 1115. engraved on it. There is an adage that says, 'Every bullet has a number on it and it could be yours.' I knew then I had found my bullet, and was convinced I would not be killed in this War.

I took the cartridge up onto the beach, and hid it near my clothes, intending to retrieve it later after another swim, however I never found it again...."

Note:

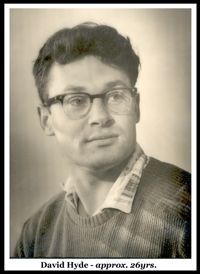

After Graham died in 1989 Audrey and my mother (Joan Hyde - nee Hudleston) found evidence in some correspondence, amongst his personal papers, that he had been awarded the Military Cross on the battlefield. (In particular, one person mentioned attending the celebration after the ceremony where he was awarded his medal). At this stage we have not proved this conclusively one way or the other but here are two recommendations:

RECOMMENDATION FOR THE AWARD OF THE MILITARY CROSS TO

SECOND LIEUTENANT GRAHAM HILL CLARENDON-HYDE

14th BATTALION AIF.

4th Brigade, 4th Division, 1st ANZAC Corps

Date of recommendation: 15th April, 1917.

Action for which commended:

For gallant conduct. On the night of the attack on the HINDENBURG LINE, to the east of QUEANT, 11-4-1917, this Officer led his platoon with great gallantry, and captured the first and second objectives. When the enemy counter-attacked, he showed great courage in the heavy hand to hand fighting, which ensued. When his platoon was decimated and forced out, he was the last to leave and made his way through heavy machine gun bullet barrage, to Battalion Headquarters, where he rendered a clear and concise report with regard to the enemy's defences.

RECOMMENDATION FOR UNSPECIFIED AWARD TO

LIEUTENANT GRAHAM HILL CLARENDON-HYDE

14th BATTALION AIF.

4th Brigade, 4th Division, 1st ANZAC Corps.

Date of recommendation: 25th September 1918.

Action for which commended:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty near ASCENSION WOOD, on 18th September 1918. Entrusted with the flank of the Battalion, and Liason with the Battalion on the left, he handled his command with considerable skill, not only maintaining the liaison under very difficult circumstances, but by clever handling of his men and gun teams, materially assisting the advance of the troops on his flank.

Entering the enemy outpost, he bombed along and established a well placed block, keeping the enemy down and out of range, thus enabling the Battalion to form up for a further hop-off. Though his Platoon was now five strong, he hopped off with the Battalion, and by his own personal efficiency with the bomb, cleaned up a threatening nest of machine guns in which ten of the enemy were killed. He set a fine example of energy and determination throughout.

Return to List

|