AN INFORMAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Chapter Four: Penally

by Monica Vincent (nee Pease)

I was four months old when my parents first took me and Purefoy to Penally, near Tenby, for our summer holiday. They liked the place so much that they went back to it every year until I was fourteen. It may seem unenterprising and dull, but we never thought so. We all loved it, and when after all those years they suddenly decided to go to Brittany for a change, Purefoy and resented this decision strongly. We went to Brittany for the next four years until the time of my father's death in 1928, and we were very happy there, but all the same La Trinite never meant as much to me as Penally had done. Nor, I think, has any other place, considered as a place, apart from the people associated with it.

We stayed in several different houses for the first few years, but finally settled down to Mrs. Skidmore's furnished rooms in Giltar Terrace. It was a small brick house in a row, expressly built for seaside visitors, but this row was the only one of its kind in the village, and our family and its connections and friends were usually the only visitors staying there. If there were any other people on the beach, we were surprised and annoyed.

Return to List

Authur and Dorothie Machen

My mother's sister, Dorl, (her name was really Dorothy) used to go there every year with her family, and they invariably stayed in the house of Mr. Jones, the station master. Mr. Jones was a friend to us all, and when we left from his station at the end of the holidays, he generally used to present each of us girls with a bunch of flowers from his garden. His begonias were particularly fine. He could speak Welsh, and in fact his English wasn't very good. Apart from him, I don't think we knew any Welsh speakers.

Dorl's husband was the writer Arthur Machen, an imposing figure in a black cape, with long white hair and a curly pipe. He was rather remote, but not unfriendly. While the rest of us went down to the beach, he used to sit and meditate on top of a certain sand-hill, which we called Arthur's Mount. Perhaps he was planning his next book. Occasionally he would gather all the children together, toss a handful of pennies among the bracken and short grass on the dunes, and let us scramble for them. We liked this. He did not bathe and was not fond of walking far. He preferred to sit about and think or talk. He must have been quite elderly when we first became aware of him - perhaps about fifty or sixty.

His wife Dorl, who was his second wife, was much younger than he was, but she had the habits and tastes of a middle-aged woman. At the same time, she was good with children. She was stout and very good-natured. Her conversation amused us, and she had a repertoire of music-hall songs which she used to sing in the appropriate manner, to our great delight. She had been an actress before her marriage, but with Frank Benson's Shakespearean company, not on "the halls".

Their son Hilary was the wrong age for us. He was too young, and generally a nuisance. Uncle Frank, my mother's brother, used to admonish us to "be kind to Hilary" - in a special voice. But I am afraid we did not usually obey him. He was notoriously greedy when we went to tea-gardens on excursions, and his parents did not correct him.

Their son Hilary was the wrong age for us. He was too young, and generally a nuisance. Uncle Frank, my mother's brother, used to admonish us to "be kind to Hilary" - in a special voice. But I am afraid we did not usually obey him. He was notoriously greedy when we went to tea-gardens on excursions, and his parents did not correct him.

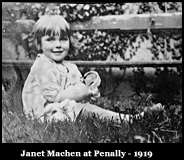

When I was about eight, and Hilary about five, Dorl had another child, Janet. She was a charming little girl, young enough for us to mother, and we never found her irksome. Poor Hilllary was the wrong age and the wrong sex, but not really an objectionable child.

Return to List

'Frank Hudleston'

Uncle Frank was separated from his wife and lived a bachelor life, but he and his daughter, Joan, used to come to Penally. She was between Purefoy and me in age. I was friendly with her in those days, but far more so after we grew up. She and Uncle Frank stayed at Mrs. Osborne's, another house in Giltar Terrace. Joan and her father were very good friends, and used to play all sorts of games together; one in particular, about an imaginary person called Looney, went on for years. Uncle Frank was a whimsical humourous man, very fond of children. We loved his jokes usually, but there were times, as I got older, when I wished he would sometimes be serious. (I myself was very serious). I think Uncle Frank had a certain likeness to Edward Lear.

Joan was also fond of jokes and laughter, but it was possible to establish relations with the person behind them. With Uncle Frank there seemed to be an impenetrable fašade. Perhaps it was a defence that he put up to hide his unhappiness about his broken marriage.

Joan was lively, gay, a ringleader among the children, and very clever at drawing, painting, and writing poems.

Return to List

The Angels

These were the regular visitors to Penally for many years. But sometimes other people came, and joined up with us. It started with the Angels: Mrs. Angel and Marion and Heather; they came to stay with their aunt, Miss Angel, who had a large house called Glan-y-Mor in the village. The girls were about the same age as ourselves, and as it was impossible to ignore them on the beach, we made friends with them. They began to come every year, and took lodgings in Giltar Terrace. We all used to go about in a crowd. Heather afterwards became a film actress, but there was nothing very remarkable about her when we knew her; she was just a lively child with a mischievous look in her eyes, and a rather pretty small freckled face, and dark hair. Marion was more demure.

These were the regular visitors to Penally for many years. But sometimes other people came, and joined up with us. It started with the Angels: Mrs. Angel and Marion and Heather; they came to stay with their aunt, Miss Angel, who had a large house called Glan-y-Mor in the village. The girls were about the same age as ourselves, and as it was impossible to ignore them on the beach, we made friends with them. They began to come every year, and took lodgings in Giltar Terrace. We all used to go about in a crowd. Heather afterwards became a film actress, but there was nothing very remarkable about her when we knew her; she was just a lively child with a mischievous look in her eyes, and a rather pretty small freckled face, and dark hair. Marion was more demure.

The Angels used to bring friends with them some years, called Robertson; they added two more children to the gang. One year there were as many as thirteen kids: Purefoy, me, Joan, Hilary, Janet, two Angels, two Robertsons, Hilda Hunter and three Lidderdales.

Return to List

Competitions

To keep all these children occupied and happy, the grown-ups organised a vast competition, with a prize-giving at the end of the holiday. (We usually stayed for a month, in those spacious days.) Prizes were offered for the best collection of shells, and for several different classes of drawings, paintings and poems. It must have been difficult not to give all the prizes to Joan, because she was the only one with any real talent. Purefoy won the prize for shells every year, not only because she could not draw, but because her collections really were the best. These competitions were held for several years and we enjoyed working for them very much, and really tried to do well.

But one evening when I was supposed to be asleep, I overheard the grown-ups talking on the terrace below ray bedroom window. They were discussing who were to be the winners, and they were arranging things so that every child got a prize for something. I was deeply shocked. I had imagined that the prizes were awarded for real merit, and this system of prize distribution seemed to me dishonest and unfair. Next day I said as much to my parents. 1 probably put it bluntly, for they were much annoyed and thought me stupid and ungrateful. They did not see my point of view and I did not see theirs, though I do now. Anyway, that was the end. No more competitions were held after that. It is possible, of course, although I didn't think of this at the time, that the grown-ups were getting bored with the whole business. But we were not.

Return to List

General Activities

The days used to pass very pleasantly. In the mornings we usually walked over the Burrows to the beach, and settled down near the pebble ridge. The grown-ups would read the paper, smoke, and sometimes paddle or bathe. The children used to bathe in almost all weathers. I can remember running down to a distant sea with the wind whistling round me much more often than I can remember bathing on a really hot day. The heat seemed to be reserved for the afternoons, when we had a long steep climb up to the cliff-tops for our daily tea picnic. This was the usual routine. Sometimes it was broken by a visit to Manorbier by train, or to Pembroke or the Stack Rocks in a hired gig, or to Caldey Island in a boat from Tenby, which we reached by train. The fare to Tenby, for a child, was twopence. Whatever we did and wherever we went we enjoyed it, and the month slipped by all too quickly.

Return to List

Changes

Penally, like Harts, remained almost unchanged for many years. I have been back several times since my childhood. The cliffs and beaches are just as beautiful as we used to think them, and the place was unspoilt and largely unknown until the Severn Bridge was built, which opened it up to a large number of motorists. The last time I went back I got a nasty shock: the station had completely disappeared; the railway which we used to love was for goods only; Mr. Jones's house had been spared, but it was no longer connected with the railway; the farm had gone; and, worst of all, a horrible trunk road had been built across the Burrows. Our dear empty beach was overrun with people. There was just one saving grace: as the road westwards from Tenby no longer went through Penally village, the village with its green and its church and its two pubs had become a quiet and peaceful backwater.

My parents and all the uncles and aunts are, of course, all dead now, and so is Purefoy (I am writing in 1979); and another of the children, Joan, is never likely to see Penally again, because she lives in New Zealand, where in the course of time she has become a wife, mother and grandmother.

Return to Top

|