|

|

MADAME LITVINOV - née IVY LOWENGLISH-BORN WIFE OF THE SOVIET AMBASSADOR, WHO HAS CHARMED THE WASHINGTON DIPLOMATIC SET, WRITES A CLOSE-UP OF HERSELF.(LIFE, Oct. 12, 1942)

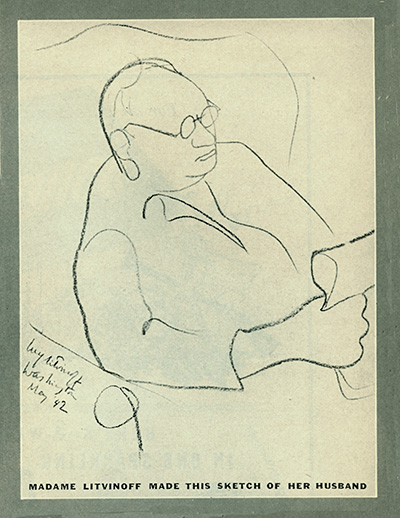

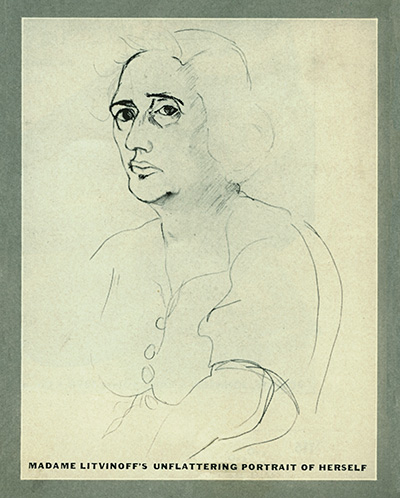

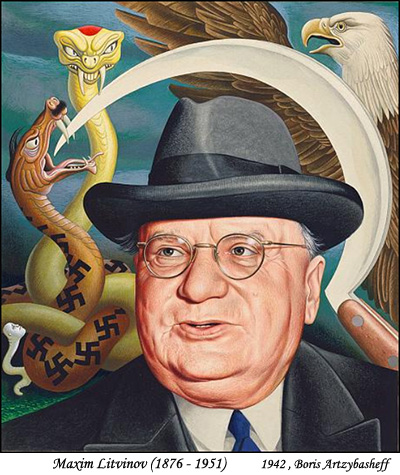

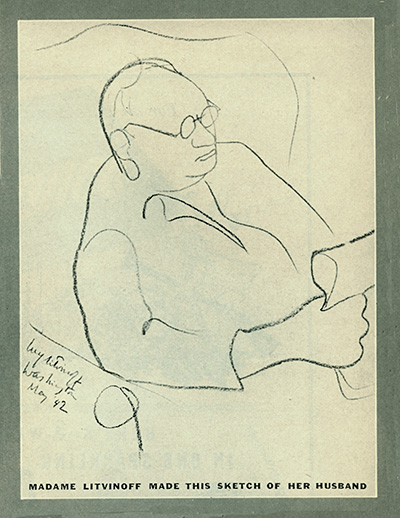

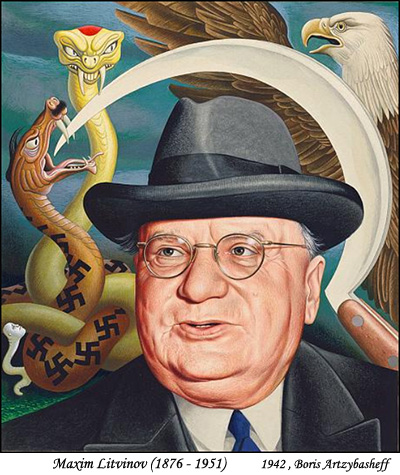

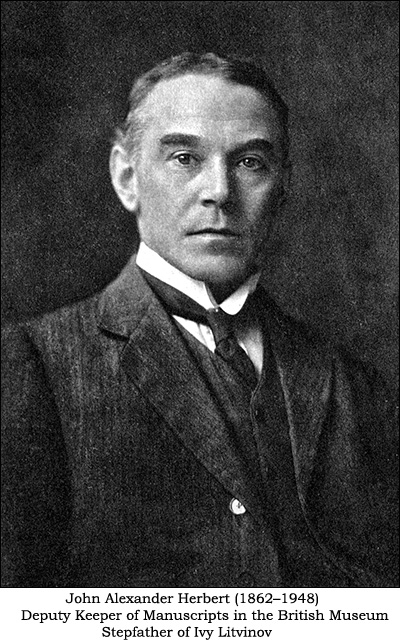

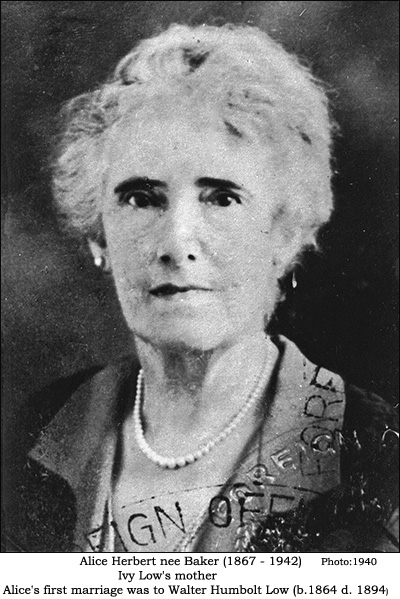

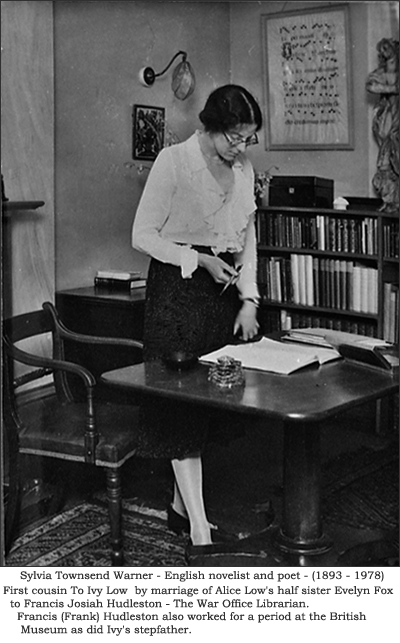

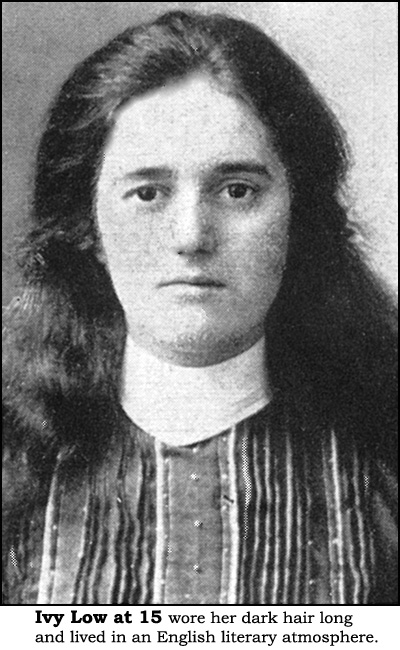

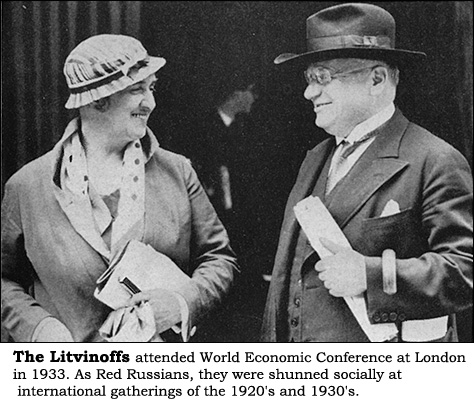

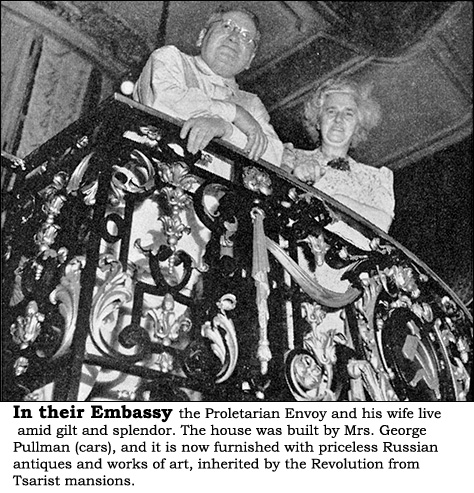

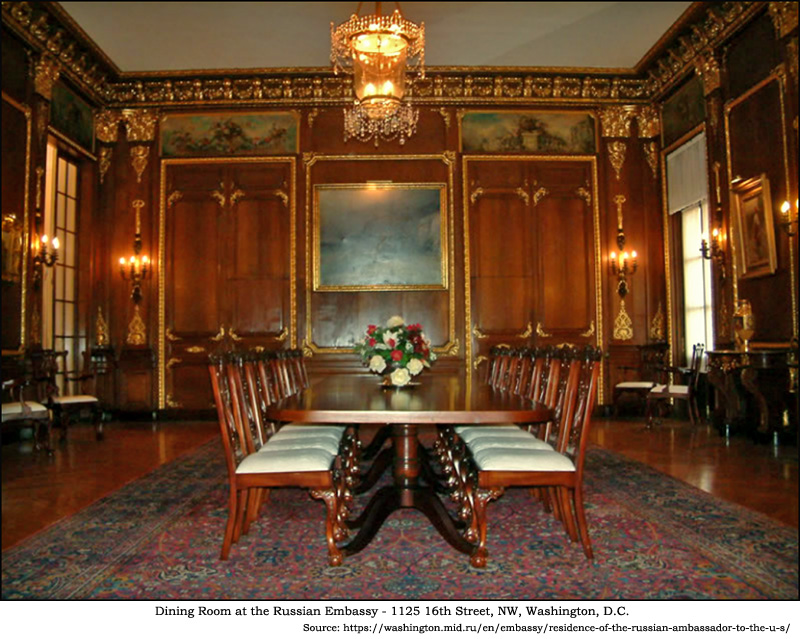

This may be due in some part to the wave of enthusiasm for Russia. But mostly it is a personal triumph for Madame Litvinoff, whose wit and charm enliven the traditional dullness of Washington social events. Instead of assigning a writer to do a close-up of Madame Litvinoff, LIFE asked the distinguished lady from Moscow to write it herself. She has signed it Ivy Low, her maiden name as a girl in London, where she was born. Besides being an accomplished writer, Madame Litvinoff is an artist who spends much of her spare time making sketches like those on this page. The Litvinoffs, Maxim and Ivy, arrived in Washington (he for the second time, she for the first time, as they say of Hollywood marriages) on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, and are as likely to "Remember Pearl Harbor" as any American. Madame Litvinoff settled down quickly to the plush and gilt splendors of the house on 16th Street. She is used to houses like this—it seems to be the sort of house revolutions tend to inherit everywhere, she says. America didn't take any getting used to. The people talk English and that was all right with Madame L., who, as the press never tires of telling the world, is "the English-born wife of the Soviet Ambassador." She took the importunities of the gossip-gals, and a fair-sized fan mail, in her stride, and got down to the real business of an ambassadress—"visits, like those of angels, short and far between." But the visits were returned, and in the meantime there were dinners, receptions, and speaking at Russian War Relief meetings, so Madame Litvinoff was kept plenty busy her first winter in Washington. Ambassadresses are not only harmless, they are necessary. At social functions they have the heavy end to hold, ambassadors tending to leave the business of charming to their wives, while they themselves concentrate on a few persons of special interest at the moment. But there are no unimportant people for an ambassadress. Everyone is important. Madame Litvinoff gets away with this part of her job by never thinking about it. She just likes people, that's all. She has a bad habit of saying what she thinks, but that seems to be all right in Washington. When she was at the Economic Conference in London, a Tory gentleman said to her, after the opening speech delivered by King George V in French: "Wasn't the King's speech good?'' "Not bad, for a king," replied Madame Litvinoff, somewhat disconcerting her husband, who overheard the conversation, and blowing the Englishman to the other end of the room, where he stayed as long as the lady from Moscow remained. But Americans seem to be pretty tough. You can say what you like, Madame Litvinoff thinks, and they don't mind. Though she feels more at home among writers and artists, Madame Litvinoff moves over the parquet floors of embassies with what Tolstoi calls "that air of unconcern, indifference and benevolence towards all, which cannot he acquired." She is always open to the idea that the person she is talking to is an interesting human being. Once she found herself entirely surrounded by Supreme Court Justices, and had the time of her life. And a conversation with a Senator about music had notable results. You never can tell. Just the same, diplomatic life is exhausting and leaves very little time for other things, especially when it has to be combined with half-a-dozen appearances in a season on platforms throughout the country. With the summer, social engagements grew beautifully less, the fan mail dwindled to almost nothing, the lady journalists found fresh subjects for their columns, and Madame Litvinoff had learned to say NO to people who wanted her to speak about the "Women of Soviet Russia" one night in Los Angeles and the next in Toronto. She found herself suddenly free to live her own life— which means drawing and writing and going to New York. Writing is her basic avocation ("I regard myself as more or less of a writer"), but drawing had long become a forgotten childhood aspiration by the time Madame Litvmoff arrived in Washington. A chance meeting in New York with a drawing teacher, who helped her as none had ever done before, revived in Madame Litvinoff the old longing. She has been wanting to draw ever since she was a child, but somehow it never came off. It has never been so near coming off as now, for in Washington she found a teacher of profound experience and artistic culture who seemed to understand all her difficulties. She began to draw three or four hours a day, working hard to make up for lost time, sometimes in Washington's Art Gallery, and sometimes getting a professional model to pose for her in the Embassy. She kidded herself along all summer that when winter came she would go to art school, but when fall came she realized it would probably be impossible. Art is notoriously long, and demands a concentration and regularity hardly compatible with diplomatic life. Ivy Low, the future Madame Litvinoff, was born in Bloomsbury, the London district made famous by the English Victorian writers, even before its very name became synonymous with the literary coteries which sprang up in the 1920's. But Ivy was born in 1889, and Bloomsbury had then gone down in the world since the days when Thackeray's "nabobs" and great physicians peopled its porticoed mansions, and had become a region of furnished lodgings and boarding houses. Her father and mother in their modest lodgings might perhaps be regarded as unconscious forerunners of the great literary invasion of the present generation, for they were both writers and moved, as soon as they got to London, in an atmosphere of ink and paper. Her father, a philologist forced to turn first schoolteacher and then journalist in order to support a growing family, edited, with H. G. Wells, the Educational Times. The two of them, as Mr. Wells himself told Madame Litvinoff many years afterward, contributed the entire contents. Her father also compiled English textbooks for examination and did the first translation into English of the work of the Norwegian writer Björnsn, specially learning Norwegian for the purpose. This crushing burden seems to have been too much even for his splendid mind and constitution, and he died at the age of 29 of pneumonia. His death changed the exclusively literary atmosphere a little, but not much, for Madame Litvinoff's mother never abandoned the writing career on which her first husband had embarked her, and her second husband, J. A. Herbert, if not a man of letters, was a man of learning. And he worked in that citadel of learning, the British Museum, so even when the family moved west, Bloomsbury was their background. |

|

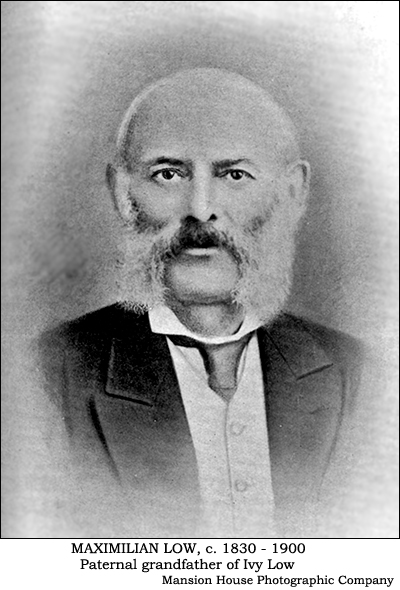

Madame Litvinoff's stepfather was (and still is) an expert on illuminated manuscripts. Even now, an old man surviving his wife, bombed out of his London apartment and far from his beloved Museum, he works daily on an ancient, partially burned manuscript, which can only be deciphered with the help of X-rays. Madame Litvinoff attributes much of her lasting interest in art to an early familiarity with the exquisite designs on the margins of these parchment missals and breviaries. Visiting savants from foreign countries frequently came to the Museum to consult the English expert, and Madame Litvinoff’s stepfather used to converse with them in Latin, like the learned men of the Middle Ages, and for the same reason — because they did not know each other's language. Very often these foreign savants were brought to dinner in the distant suburb of London which was now the home of the family. As the three girls could not even talk Latin, the language of smiles and passing the salt was their only means of communication. But after dinner the song book would be brought out, and everyone would gather round the upright piano and sing French or German folk songs, while Ivy sat at the piano and played accompaniments. Later, when she found herself in foreign parts, she had ready-made phrases in French and German at her tongue's end. All Madame Litvinoff's relatives on her father's side have been "intellectuals" (writers, teachers, and psychoanalysis) but her mother, who published a book of verse and three or four novels, seems to have been a white sparrow, with no family history to account for her literary gift. Madame Litvinoff's earliest memories are of piles of review books standing against the wall in the dining room. When the piles took on a sway-back, she helped her mother to make bundles of the books, and very often accompanied her to the Charing Cross bookshops at which they were sold. (Those were the days in which reviewers got more from selling books than from reviewing them.) Little Ivy got splendid practice in wrapping books in brown paper and making slipknots. She remembers also, with respect, the careful register her mother kept of every hook that passed through her hands, with the date of reception, the date of review, and the date, place and amount of sale. Unfortunately the inoculation of these careful habits did not take, and Madam Litvinoff herself never keeps a copy of a letter, and can hardly be persuaded to keep her engagement book up to date. Madame Litvinoff's stepfather was (and still is) an expert on illuminated manuscripts. Even now, an old man surviving his wife, bombed out of his London apartment and far from his beloved Museum, he works daily on an ancient, partially burned manuscript, which can only be deciphered with the help of X-rays. Madame Litvinoff attributes much of her lasting interest in art to an early familiarity with the exquisite designs on the margins of these parchment missals and breviaries. Visiting savants from foreign countries frequently came to the Museum to consult the English expert, and Madame Litvinff’'s stepfather used to converse with them in Latin, like the learned men of the Middle Ages, and for the same reason — because they did not know each other's language. Very often these foreign savants were brought to dinner in the distant suburb of London which was now the home of the family. As the three girls could not even talk Latin, the language of smiles and passing the salt was their only means of communication. But after dinner the song book would be brought out, and everyone would gather round the upright piano and sing French or German folk songs, while Ivy sat at the piano and played accompaniments. Later, when she found herself in foreign parts, she had ready-made phrases in French and German at her tongue's end. All Madame Litvinoff's relatives on her father's side have been "intellectuals" (writers, teachers, and psychoanalysis) but her mother (Alice Low née Baker - second marriage known as Alice Herbert), who published a book of verse and three or four novels, seems to have been a white sparrow, with no family history to account for her literary gift. Madame Litvinoff's earliest memories are of piles of review books standing against the wall in the dining room. When the piles took on a sway-back, she helped her mother to make bundles of the books, and very often accompanied her to the Charing Cross bookshops at which they were sold. (Those were the days in which reviewers got more from selling books than from reviewing them.) Little Ivy got splendid practice in wrapping books in brown paper and making slipknots. She remembers also, with respect, the careful register her mother kept of every hook that passed through her hands, with the date of reception, the date of review, and the date, place and amount of sale. Unfortunately the inoculation of these careful habits did not take, and Madam Litvinoff herself never keeps a copy of a letter, and can hardly be persuaded to keep her engagement book up to date. Since she has been in Washington, Madame Litvinoff has been constantly reminded of her uncles, Sir Sidney Low and Sir Maurice Low. They were both journalists, the former in London and the latter, as correspondent to the London Morning Post, in Washington. Each in his separate sphere seems to have made dents in female hearts, and when she first came to Washington Madame Litvinoff had to get used to meeting elegant middle-aged ladies who had been "so fond of your Uncle Sid,” or, still more often, "your Uncle Maurice.” Madame Litvinoff thinks her uncles were all right, though she is sure neither of them was half so brilliant as her father. Madame Litvinoff thus came by her literary gift honestly. Her first creative effort was, like most people's, verse. She has had poems printed in several English papers, the Observer, Evening Standard, and in one or two weeklies, Country Life and The New Statesman. She says they were quite neat, but nothing special. During this lyrical period of her life she was always buying a paper in the street and opening it eagerly as she walked away, to see if her latest poem had been accepted. She was sometimes jeered at by rude men, who supposed she must have bet her shirt on a horse. In her early 20’s she produced her first novel, Growing Pains. She docs not think it was a good novel, or even a novel at all by her present standards, but believes it was the cause of quite a few other books of the same sort—formless chronicles of childhood into adolescence, and early marriage. She is not at all proud of her second book, The Questing Beast, and once lent it to a friend with the words: "It makes me blush, but it won't make you." Still The Questing Beast was more of a story than Growing Pains and showed a certain power of creating people out of words. Then she got married and didn't write anything at all for more than a decade, when she brought out her third book, His Master’s Voice. His Master’s Voice was a mystery story, the plot hanging, believe it or not, on a cracked phonograph record. Madame Litvinoff is less modest about this book than about the others. In fact she was once heard to describe it as "quite moderately not so badly written." She believes it is the only detective story with a Moscow background. She's a bit puzzled how she came to write it as she's not really a detective-story fan herself. |

|

|

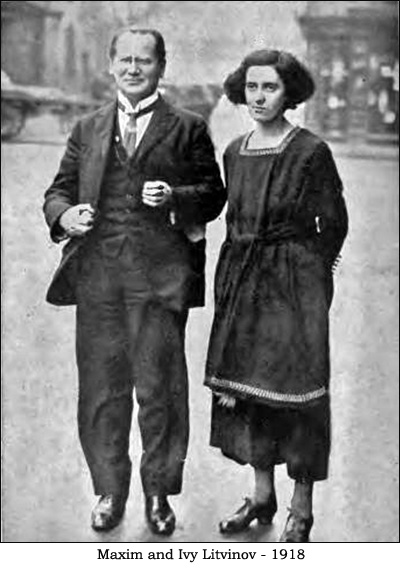

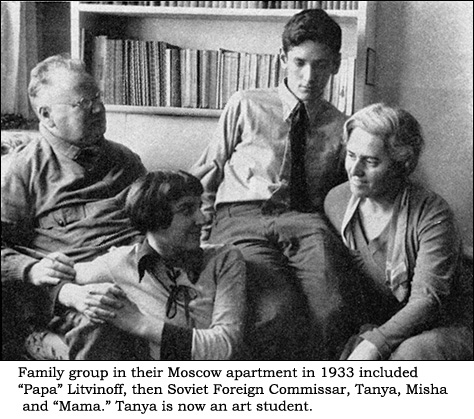

A disciple of Marx discovers Jane Austen Ivy Low met Maxim Litvinoff in Hampstead, London, the favorite residence of Russian emigres fleeing from tsarism. Hampstead is the Greenwich Village of London, but has retained far more of its oldtime flavor than the Village has. When the Litvinoffs were married in 1916, two years after the outbreak of World W'ar No. I, English Ivy Low became a friendly alien. Up to the outbreak of the 1917 Revolution she lived with her husband in Hampstead, "and had a baby, and all that.” Under her husband's tuition she made a good effort to conquer the Russian language, but conjugal lessons are seldom a success. Her own attempts to imbue her Marxian husband with her special taste in English literature were a good deal more successful than his to teach her Russian, and Mr. Litvinoff discovered new pleasures in reading about Miss Austen's polite spinsters, and Anthony Trollope’s parsons and politicians. D. H. Lawrence didn't go so well—his books seemed to be all about nothing to a man who had read Das Kapital. The Litvinoffs’ first baby was born about three weeks before the abdication of the Tsar and the establishment of Kerensky’s "Provisional Government” in 1917. Madame Litvinoff will always remember the day the news came. It was a misty morning in March, and the nurse came in as usual at 8 o’clock to draw the curtains. The new mother asked for the day’s paper. The nurse said there was nothing in it, just another Zeppelin raid over the East End of London, but it had been beaten back, and nothing new from the front. She had not paid any attention to events in a far-off improbable land called Russia. The first Madame Litvinoff heard of the Revolution was by phone from her husband, who had been so excited that he had got into his bath without turning the taps on that morning, stepping solemnly out to dry his dry body after a few moments soaking in the cold air of a London bathroom. The baby boy Misha was only 9 months old when the Bolshevik party came into power in November 1917, and in January 1918 Maxim Litvinoff was made First Proletarian Envoy to the Court of St. James’s. The baby was now old enough to be parked, and Madame Litvinoff went into town daily with her husband, to help with the chores around the "People’s Embassy" in Victoria Street. But in August 1918 a second baby (Tanya) was born, and news came of the imprisonment of Bruce Lockhart, British envoy to Petrograd, on a charge of conspiracy against the new government. By way of retaliation Mr. Litvinoff and his staff were sent to Brixton prison, where their cells were marked "Reserved for the Military Guests of His Majesty.” Soon after, Maxim Litvinoff went to Russia, leaving behind him a young wife and two small children. Madame Litvinoff thinks these were the dullest, hardest months of her life. Fifteen months later she joined her husband in Copenhagen, where he was sent on a mission to negotiate with several foreign governments, and by 192.1 the whole family was established in Moscow. For the first two years of Madame Litvinoffs’ life in Moscow the children were very much on her hands. They went to kindergarten, it is true, but they always seemed to be coming back. The Litvinoffs lived at first in what is now the British Embassy in Moscow, a house with magnificent halls and staircases, and rooms full of art treasures and junk. Every night while the children were little, Madame Litvinoff would visit one of these halls of splendor, paper and pencil in hand, and when Misha and Tanya waked up in the morning there was always a "pattern” for each on the bedside table. Their part of the game was to go through the house themselves, and discover from what carpet or bit of tapestry or carved door Mamma had taken the pattern. They soon learned to retaliate, and Mamma was confronted with many a strange pattern, which it was often very hard for her to trace. Later Tanya became an art student, and believes that it was this game of patterns that gave direction to her mind. Animals have always played a great part in Madame Litvinoff's life. She gets her passion for them from her English parents, and her children have inherited it from her. This is of course definitely an Anglo-Saxon trait though Madame Litvinoff has met with a great deal of real feeling for animals in Russia. Her husband's chief idea when he sees an animal of any sort is to feed it, and the family dogs have always been as stout as their owners came to be in later life. Experiment in teaching English to Russians As her boy and girl grew up, and became more and more independent of her time and care, Madame Litvinoff began to look around for something to do. There was not much diplomatic life in those early years in Moscow, and time began to hang heavy on her hands. There has never been a moment when a woman couldn’t get herself congenial work in the Soviet Union, but Madame Litvinoffs poor knowledge of Russian debarred her from many jobs which might have been of the greatest interest to her. The only work that suggested itself to one with such a strong pedagogical inheritance was the teaching of English. She began by trying to teach adults. She had up till then so little curiosity about the structure of her native tongue that when her pupils asked her awkward questions, such as “When do you use the Present Perfect?” or “How is the Passive formed?” she had to put them off for the moment, and take the questions home for consultation with her husband, who, she soon found, knew much more about English grammar than she did. The lessons went very well at first, in a Berlitz sort of way. She soon taught her students the ceiling and the stove, the nose and the mouth, and had them memorizing useful little questions and answers, so that they could ask each other: Where do you live? How old are you? What do you do? Have you any children? Is this a book?” and receive the extremely satisfactory replies: "I live in Moscow. I am 28 and I am a bookkeeper. I have two children. No, it is a box.” But the students refused to continue memorizing questions and answers when they found they were no nearer to reading the news- newspaper or understanding conversation than they had been at the beginning. "They had a very nice pronunciation," Madame LitvinofF recalls mournfully. "But they had nothing else at all. Once an inspector came and asked my best pupil: 'Arc you a man or a woman?' The pupil replied: 'No,' and when he saw me looking at him reproachfully, he tried to make things better by saying: 'No, I am not a man or a woman.' " Remembering how French and German songs at the piano in her girlhood had helped her later when she went abroad, Madame LitvinofF taught her pupils lots of English nursery rhymes. Before the class broke up in despair they all knew Polly, Put the Kettle On, and Baa! Baa! Black Sheep and I Had a Little Nut-Tree and a whole lot more. Madame LitvinofF hopes that was at least something for them. There was generally a piano in the classroom, but Madame Litvinoff was vexed to find that ten years of playing five-finger exercises in the drawing room had not equipped her to play simple accompaniments to the old songs she knew so well. Someone told her of a composer who taught harmony by a special system and she went to him and asked him how long he thought it would take her to get to the stage of improvising simple accompaniments to familiar melodics. He thought it would take about two years. And it did. Learning Russian language at 42 Then began what Madame Litvinoff calls her "Harmony Era.” Learning the rules of harmony was the toughest thing she has ever done and she was 41 when she took it up. It all had to be done in Russian and the terminology was completely unfamiliar—the very notes have different names and the comfortable scale of C is no longer an anchor. Her teacher had difficulty in realizing that a pupil who played Bach inventions with facility and the slower movements of Beethoven sonatas with the allegro played moderato had not the faintest idea what the subdominant meant. "Nothing will ever be more difficult than learning to resolve septa-chords,” she says. "I just listened to him with my head down and the moment he was out of the room rushed back to the piano and tried to do everything he had told me by memory because it seemed as if I hadn't understood a word of it." One day, after two hours of wrestling at the keyboard, the tonic, the subdominant and the dominant came rolling our, and a maid with the wonderful name of Pelagaya Afanasevna, who had been suffering in the kitchen all the time, put her head into the room and said: "Look what desire can do!” Madame Litvinoff believes a child of 8 could have learned in a year without the slightest trouble what it took this middle-aged woman two years of unending effort to master. But at the end of the two years she could improvise song accompaniments and was on the way to getting almost as knowledgeable about music as her son, who was always ready to help her out with a difficult composition. During a visit to London in 1931 Madame Litvinoff met C. K. Ogden, the inventor of Basic English, and what she calls the "Basic Era" in her life began. Mr. Ogden told her all about Basic English and her interest in teaching began to revive. When she returned to Moscow she decided to begin all over again. Everything was quite different now. Basic English makes the work a cinch for the teacher and the student really does learn something. After about a year of teaching in Moscow, she got a book out called Basic Step by Step. The title and the texts were Mr. Ogden’s but there was a tremendous job for Madame Litvinoff and her assistants in adapting the texts for Soviet aims and ideology and in supplying grammar rules in Russian and getting the right pictures. She remembers fondly the summer months in Moscow during which she and her "Basic Girls” worked on it. "We worked in two rooms with a typewriter in each," she says. "An English one and a Russian one." The rooms got so filled with galleys and typescript, all being worked on at the same time, that they dared not let the dog in. They worked like Pendennis, with the printer's devil sitting in the passage and snatching wads of typescript from them. The hours passed so unnoticeably that if it had not been for Pelagaya Afanasevna, who pried them off the typewriters every three hours and dragged them to the dining room, they would have starved. Madame Litvinoff says nobody knows what trouble is who has never tried to compile a foreign-language textbook. You’re always discovering you’ve forgotten to mention the position of the adverb in the sentence, or something, and there never seems anywhere you can push the damn things in. After the book had run into two or three little editions of 30,000 or so without making any perceptible dent on public opinion, Madame Litvinoff started on another—the book of the words for a phonograph course, complete with records. This was ever so much easier, for so much experience and classified material had already been accumulated. It ran through its editions of 30,000 at a time and the Soviet schools absorbed them all and asked for more. |

|

|

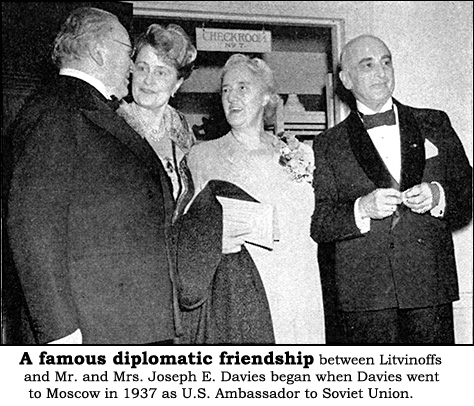

Bears and pigs at a diplomatic party Diplomatic life in Moscow had now become something to be reckoned with. Country after country had decided to "recognize” the existence of the Soviet Union and by the time the first American ambassador arrived there were dinner parties or receptions almost every evening. Ambassador Bullitt's "zoo party" will long be remembered by every Russian who attended it, for though goodness knows hospitality has always been Russia’s long suit, animals at a full-dress diplomatic function was something new to Muscovites. In the old days they said it with gypsies and vodka, but it had never before been said with baby bears. Ambassadresses and the wives of secretaries carried bear cubs and piglets about all evening, getting their dresses ruined but enjoying themselves. There were goats too, snow-white goats, and they—oh well, everyone knows about goats. With all this High Life going on, Madame Litvinoff was beginning to find it more and more difficult to be in class at 9 a.m. sharp. Something had to go and in those days it wasn't going to be Basic English. So Madame Litvinoff started out on her last Basic adventure. She turned her back on diplomatic duties and got herself appointed teacher of Basic English on the staff of one of the biggest engineering institutes in the country, the Ural Technical Institute in Sverdlovsk. But the students didn't have time to give to English, as they knew it wasn't so important as most of the other things they had to learn, and that was not much fun for their teacher who wanted to regard her subject as all-important. But there were other things. She was never lonely there: it was easy to speak to the family over the long-distance telephone and the children often paid her long visits. Sverdlovsk is about 900 miles from Moscow, but only a few hours by air, and whenever there was a holiday of a day or two Madame Litvinoff flew home. She made a special journey to see Ambassador Davies and his wife when they came to the Soviet Union. With the appointment of Ambassador Davies the American Embassy seemed naturally to take its place as the social center of Moscow, and the warm friendship that still exists between the Litvinoffs and the Davies had its beginning then. Sverdlovsk (formerly Ekaterinburg) is an old mining center, and the boys who got rich there in the 19th Century built some pretty good houses, and there is a university, two or three theaters, and a big concert hall. Since the Revolution, a few big apartment houses, a department store, several educational institutes, a musical conservatory and streetcar routes have been built, all adding considerably to the amenities of the city. A long ride on a streetcar takes you to a gigantic steel plant now probably rolling out tanks and guns to stop Hitler. There the workers' quarters arc contemporary with the plant, and the stores, schools, movie theater and municipal buildings arc all planned on garden-city lines. How to make children think they are eating candy In Sverdlovsk Madame Litvinoff began teaching harmony as well as Basic English. She taught music to whole families on the campus. First the children came. Then she coaxed the mothers in, through their pride and interest in their children, keeping them a lesson or two ahead of the kids, so they could help them in their practice. And finally some of the fathers got so interested that they asked to be taught too. The children, of course, got on faster than their parents, but Madame Litvinoff says many of the parents were very intelligent. Some of them were lecturers on the resistance of metals, or readers in chemistry, but most were housewives, whose daily marketing and floor-scrubbing, added to cooking and mending and looking after the children, left them little time or energy. But they found the time and energy somehow, these Soviet mothers, in their eagerness to keep in touch with their children and in their native Russian love of music. A year after she left Sverdlovsk a friend wrote Madame Litvinoff: "I often see your 'children.' They love to talk about 'Auntie Ivy,' and her wonderful toys and the marvelous candies and cookies she used to give them." Not a word about music, you see. But Madame Litvinoff never did give the children candies. "1 was afraid,” she says, "if I began giving them candies, they would come expecting them every time, and be unable to think of anything else throughout the lesson. As for toys, I kept a few picture books and puzzles for children who had to wait. Always the same ones, like in a dentist's parlor. They soon knew them all by heart, and usually occupied the time of waiting by playing with Me-Too, my old wire-haired terrier who had flown with me from Moscow." She supposes they translated the sweetness of music into the sweetness of candies. She left her work in the Technical Institute, and her apartment on the campus, and her rented piano, and her neighborhood pupils, and the encircling pine forest, with many pangs, after her husband left the Foreign Office in the spring of 1939. The family, re-united, plus a daughter-in-law (son's wife), spent the two years before Maxim Litvinoffs appointment as Ambassador to the United States, in quiet occupations, mostly in their country house 17 miles from Moscow. When the schools opened the whole family migrated to their Moscow apartment, but spent long weekends in the country. The two years passed in family bridge, reading and music, and country walks with the dogs—Silky, Maxim Litvinoffs adored black spaniel, Me-Too, and a strangely assorted crew of young dogs and pups, some the offspring of carefully picked sires, others the fruit of an illicit union of Silky and Me-Too. Madame Litvinoff found two pupils in the country—13-year-old Svetlana, the gardener's daughter, and her 65-year-old husband. There was a certain friendly rivalry between them, but both did very well, and Madame Litvinoff was always wakened in the morning with a spirited performance by the older pupil of Katy-Did, She Did! and Home on the Range. A very good number was My Country,'Tis of Thee, executed by the former Minister for Foreign Affairs and his wife. In his unusual leisure, Maxim Litvinoff even tried taking up Russian lessons with his wife again, for though her Russian had increased greatly in bulk in the past 10 years, and she had acquired a remarkable facility, she still made a foreigner's mistakes. Both teacher and pupil, were, however, mortified to discover that the lessons were no help. Madame Litvinoff acquitted herself splendidly — there wasn't a grammar rule she did’t know, and she flew through all the exercises in the book. She just couldn't apply her knowledge in speech. She thinks it’s not her fault. No language should have so much grammar. Toward the end of the second year of Maxim Litvinoffs retirement, a grandson was born. Madame Litvinoff says he was just an ordinary baby, but nice. She left him just as he had begun to stump about the room and become an object of his grandpapa’s generosity at table (transferred from the dogs). He had already become adept at licking caviar off bits of toast and coming up for more. (Caviar was less of a luxury than butter in those days.) Madame Litvinoff thinks hers has been a good life, with a streak of irony running through it—fate giving a queer little twist to the thread before snapping it off. She’s had most of the things she wanted to have. First she wanted to draw—well, she’s had plenty of opportunity to draw, and even has drawn, and there’s nothing to prevent her from going on drawing. Then she wanted to write, and she did write, and even got her writings published. She wanted to marry, she wanted to have children, she wanted to travel—and got all those wants in exactly that order. When she wanted to master harmony she found the one person who could teach her just when she wanted it. And her latest want was for a grandchild, and the grandchild came. The twist in the thread is the things she didn’t want, the things which lots of women would give their cars for parties and clothes and champagne and caviar and "social position." But Madame Litvinoff doesn't like parties and clothes and champagne and social position. (She doesn't mind caviar.) |

|

|

|

|

|

|